|

||||

|

History: Tribe warmed up to difficult relocation decision

1/2/2013 8:56:16 AM

By Ross Schneidmiller

Liberty Lake Historical Society

As Joset suspected, the tribe, including its headsmen, did not like what he was saying. They had spent years clearing the land, building their houses, barns and rail fences. This was to be a permanent home for their children for all time. This discussion was especially hard for those who lost their buildings by Colonel Wright's fires. It had been four and a half years since the Indian wars of 1858. They had worked long and hard to rebuild what they had lost. Now they were being told to leave it all behind and move to the Palouse.

Andrew Seltice, a sub-chief at the time, said to Joset, "Unless you give us some very good reasons, we won't even think of leaving our homes after all these years of work. ... Our Creator has blessed those of us in the Spokane Valley with thousands of horses and cattle. We can't find another valley that will furnish year around feed, summer and winter. In the valley, when the ground is covered with snow, all the stock have to do is paw the ground two or three times to shove the snow aside. Then the heavy grass jumps up out of the snow, and all the stock feed to their satisfaction. We would have to feed our stock all winter in the Palouse. So far, we don't have the equipment to plow up enough land to raise hay for wintertime."

Father Joset tried to explain further, but was cut off by Peter Wildshoe, who said, " You already explained enough! We are not going to move to a different location."

The priest felt if he would be allowed to explain everything to the Tribe, they would not be upset, but he did not get his chance. The next day, the Coeur d'Alenes left early for their journey home - disturbed with the way Holy Week ended.

During the next year, Joset's words began to resonate with the leadership of the tribe. It became apparent to Seltice and others that the Coeur d'Alene's ways would need to change. Instead of gathering and hunting, they would need to depend upon farming and ranching for their survival. The more progressive members of the tribe looked over the Palouse and saw the benefits of moving. Their concern about plowing enough land was diminished when they saw how good the soil was and how easily it could be cultivated.

|

Did you know? The Development of a Community |

Vincent felt Seltice was better suited for leading the tribe to the Palouse and would soon relinquish his right as Head Chief of the Coeur d'Alenes to Seltice. Joset agreed and said, " When he (Seltice) moves, you should all follow and imitate him."

The entire tribe had the highest respect for Andrew Seltice. He had gained great wealth from his hard work and had long been generous to all his tribesmen. Seltice, accepting this honor, stood and said: "Many of us are already working the land, improving our machinery and also enlarging our fields. But the soil of the Spokane Valley, Headwaters and Mission Valley can not be compared to the soil of the Palouse, which has no gravel nor rocks at all. The valley of the Palouse is broad. It has the finest soil and also the finest timber on the north end. It has plenty of room for all of us."

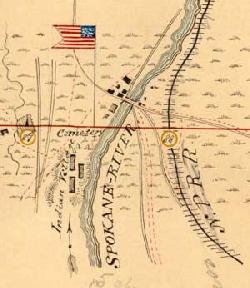

It would take several years for the relocation to take place. Seltice, Wildshoe and Tecomtee staked their claims near each other by the present sight of Tekoa, Wash. They selected land with creeks that had year-round running water. These Coeur d'Alenes from the Liberty Lake area decided not to move their stock right away. They would let their horses and cattle roam the Spokane Valley until they could raise enough feed for their stock in the Palouse to sustain its harsher winters. Those who ignored Seltice's wisdom to plow enough ground to have plenty of hay and grain lost much of their stock in the harsh winter of 1871. Learning from their losses, they built their barns and sheds next to the plentiful timber where the stock could find protection in harsh conditions. The Coeur d'Alenes had encountered many challenges and changes but were now moving forward under strong tribal leadership.

Ross Schneidmiller is president of the Liberty Lake Historical Society. This is the first article beginning a third year of monthly articles produced by the LLHS. This year's series theme is, "The Development of a Community."